UPDATES! 15 May 2025

An audio version of this post is now available here.

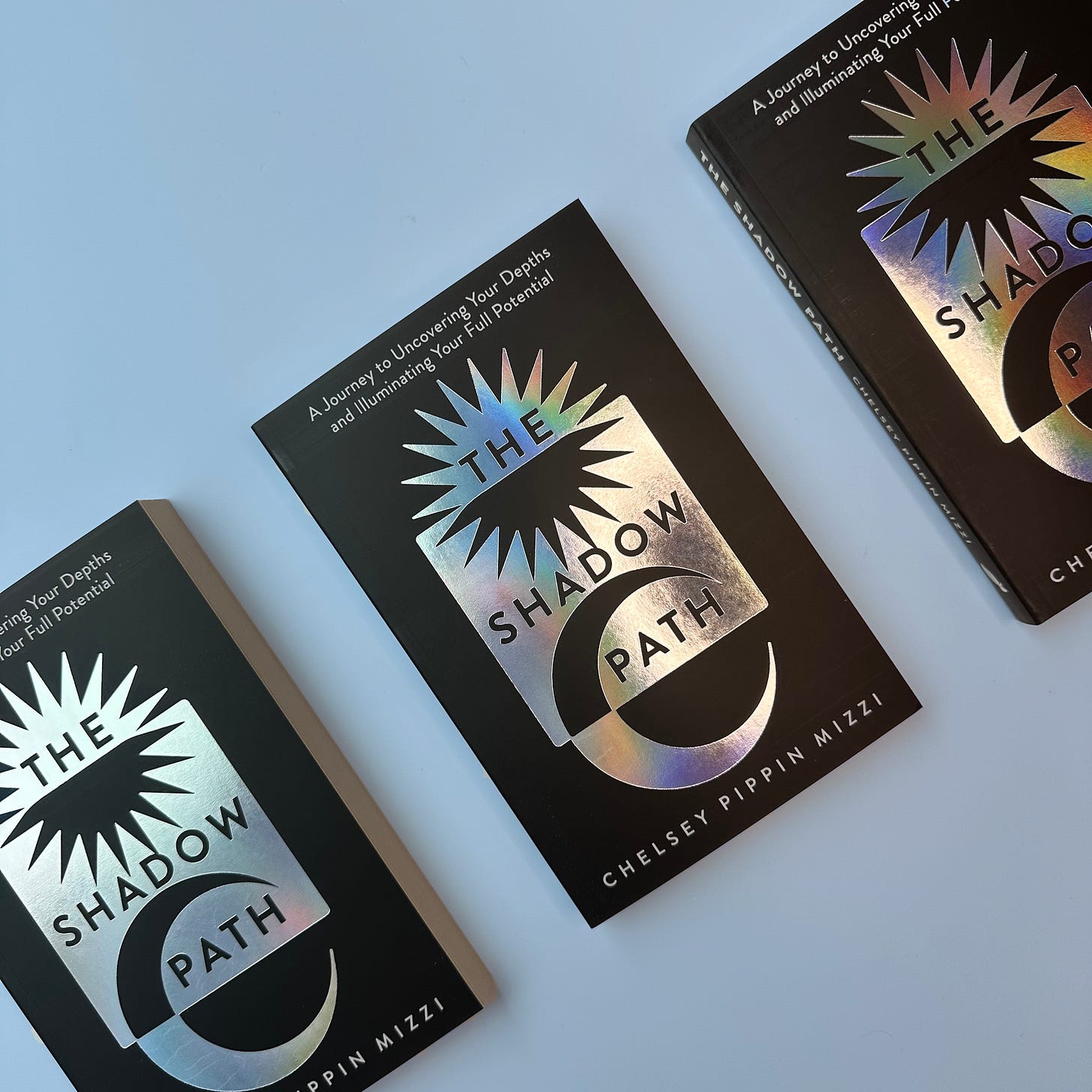

The essay below touches on Jungian psychology and shadow work as a creative practice — since writing it, I published a whole book on the topic, some of the words from this piece even found a home in the final manuscript!

The Shadow Path is out now.

I.

A little over ten years ago, an episode of Mad Men capsized my creative identity.

In the scene, (at least as I remember it) Don Draper’s second wife Megan, an aspiring actress, is distraught after a string of failed auditions. She seeks out her mother, Marie, for comfort. Bad call. Marie’s assessment is the worst thing, and maybe some of the most effective writing I’ve ever come across. She tells her daughter: “This is what happens when you have the artistic temperament but you're not an artist.”

The sudden onset of doubt that line triggered for me was staggering.

It’s not that I’d never doubted my artistic ability before. Trust me, I did it — still do it — all the time. Why else was I watching Mad Men instead of writing my Master’s dissertation, except to momentarily outrun the haunting question: what if it’s bad?

But I’d never doubted my artistic identity before.

Could Megan and I be the same? Were we deluding ourselves, confusing our sensitive, expressive temperaments with artistic callings?

Worrying that I was bad at something was so different from fundamentally not being something at all. It was losing the key and having to call a locksmith, versus having no claim to the house in the first place.

Up until then, I may never have been sure if the house had any value, but I’d always felt certain it was, at least, mine.

Megan doesn’t make it as an actress.

Like the first Mrs. Draper, she becomes something of a cautionary tale. Her softness, sensitivity, and emotionality are weaknesses she can’t overcome. Her “artistic temperament” is a hindrance to her creative ambitions. She’s painted as a spoiled, weak-willed fraud. Compare this to the Mad Men heroine Peggy Olson’s journey from unassuming secretary to hard-boiled copywriter. Real creatives, the writing of Mad Men asserts, are tough, but they are also natural talents. They don’t need support or nurturing; they need a challenge. If you don’t “have it”, you’ve only deluded yourself into feeling like you do. And as Megan’s trajectory proves, that’s just embarrassing for everyone.

The viewer is left to assume that Marie was right about her daughter.

I was left to internalize that she was right about me.

II.

In The Artist’s Way, the world-famous 12-week program for creative recovery, author Julia Cameron includes a passage that Megan and I could have used back when Marie was bullying us both:

One of our chief needs as creative beings is support. Unfortunately, this can be hard to come by. Ideally, we would be encouraged first by our nuclear family, and then by ever-widening circles of friends, teachers, well-wishers. As young artists, we need and want to be acknowledged for our attempts and efforts as well as for our achievements and triumphs. Unfortunately, many artists never recieve this critical early encouragement. As a result, they may not notice they are artists at all.

Parents seldom respond, “Try it and see what happens” to artistic urges issuing from their offspring. They offer cautionary advice where support might be more to the point. Timid young artists, adding parental fears to their own, often give up their sunny dreams of artistic careers, settling into the twilight world of could-have-beens and regrets. There, caught between the dream of action and the fear of failure, shadow artists are born.

I obviously agree with a lot of what’s said here — if creativity were a thing more commonly nurtured and supported in society, more people would feel comfortable exploring their artistic passions. And that’s a good thing — even if their artistic ambitions only ever lead them to make “bad” things by professional standards1.

And yet, I abandoned my first attempt at The Artist’s Way thirty pages in - just a handful of paragraphs after reading the above quotation.2

After first introducing the term “shadow artist,” Cameron goes on to outline examples of people who fit the profile: a wealthy art collector who bankrolls other artists because he’s too afraid to create for himself, a dissatisfied therapist who abandoned her artistic dreams and resents her work, a movie buff who hero-worships his artist girlfriend, but refuses to take a film class because in his mind “not everyone can be an artist”.

I appreciate that Cameron argues the opposite: Everyone can be an artist if they’re brave enough to pursue their dreams. It’s a direct counterpoint to Mad Men’s Marie’s cruel thesis that wanting to be an artist may just mean you’re delusional. I cheered when Cameron wrote: “We tell ourselves that real artists can survive the most hostile environments and yet find their true calling. That’s hogwash.”

But then, Julia swings too far away from her goal of empowering artists to pursue their dreams. This is where she starts to lose me:

[Shadow artists are] hiding in the shadows, afraid to step out and expose the dream to the light, fearful that it will disintegrate to the touch.

Shadow arists often choose shadow careers — those close to the desired art, even parallell to it, but not the art itself. … Intended fiction writers often go into newspapering or advertising, where they can use their gift without taking the plunge into their dreamed-of fiction career. Intended artists may become artist managers and derive a great deal of secondary pleasure from serving their dream even at one remove. 3

Here’s my problem: In the course of making her case that everyone deserves to explore their artistic dreams, Cameron inadvertently dismisses a swathe of very valid creative identities. She effectively births a whole new army of shadow artists by creating a hierarchy that denotes what kinds of creative pursuits get to be pure, and which ones are relegated to shadow, based on her very narrow definition of what it means to achieve a creative dream.

On my first reading of The Artist’s Way, I was stung to learn that by Julia’s estimation, the creative work I was doing at the time apparently belonged in the shadow category.

When The Artist’s Way found me just a couple years after the Mad Men incident, I was in my own Peggy Olson era: cutting my professional writing teeth as a staff writer at BuzzFeed. I was also (and remain) an aspiring novelist.

Understandably, Cameron’s jab at intended fiction writers working in media felt personal. It brought all my cruelest doubts to the surface and introduced shame into my professional identity where previously there had been only pride, a sense of possibility, and growth.

It was hard to entertain the assertion that what felt like a windfall — a paid, full-time creative writing job — was, according to Julia Cameron, nothing but a fear response.

But I was twenty-five. I was just clawing my way out of my first, embarrassingly TV-triggered artistic identity crisis. I was working in a highly competitive environment that wreaked its own havoc on my creative confidence.

So, I took it to heart.

I wasn’t an artist, I was just a girl with a MacBook Air and a lot of feelings, distracting herself, and pretending.

I have heard from creatives who felt deeply seen and liberated by Julia Cameron’s concept of “shadow artists”. I understand that, as she points out, there are people who have been so indoctrinated to believe that pursuing art is frivolous and financially irresponsible that they’ve never given themselves permission to claim artistic aspirations at all, despite a genuine love for all things creative. I’m happy that this section of the book can speak to them.

I also think it’s disingenuous, and frankly a little delusional to frame certain creative professional paths as “shadow careers”. In this economy???

It goes without saying that for many people, artistic pursuits are a privilege they can’t afford — though Cameron does, in fact, say it. Twice, on two separate pages:

For many families, a career in the arts exists outside of their social and economic reality.

Many real artists bear children too early or have too many, are too poor or too far removed culturally or monetarily from artistic opportunity to become the artists they really are.

Julia argues that it’s not a sensitive, faux-artistic temperament that prevents people from pursuing art. It’s conditioning and circumstance (again, I agree.) But her prescription for this issue is overly simplistic and doesn’t really acknowledge the lived realities of the “shadow artists” she describes:

In order to move from the realm of shadow into the light of creativity, shadow artists must learn to take themselves seriously. With gentle, deliberate effort, they must nurture their artist child.

How the fuck, may I ask, can a person who has become a “shadow artist” — through either conditioning or socio-economic circumstance — learn to take themselves seriously and support themselves financially in a way that allows them the safety to nurture their inner artist child, if not by pursuing a “shadow career”?

Are we to understand that it would be somehow better to be an accountant or a plumber with a “pure” creative pursuit than a working creative in a field like journalism, curation, criticism, or publishing?4

Or is Julia making the wildly irresponsible suggestion that the only solution to having creative aspirations is to abandon all security in the pursuit of the dream?

I, for one, was not in a position to pursue writing a novel full-time. Even as a published author today, I am not in that position. But I have been operating as a full-time writing since 2014, thanks, I guess, to a fear response that nudged me toward a “shadow career”.

Despite the garden of doubt the “shadow artist” concept planted in me, where previously there had been wildflowers of opportunity — here’s how I’ve come to realise that my squiggly “shadow career” path has supported and elevated me to creative success:

Working as a staff writer covering lifestyle, travel, and literature taught me about the world. It taught me about books, and publishing, and it taught me how to write, how to edit, how to meet a deadline. It connected me with authors5, got me access to literary festivals, and helped me see just how my longest-held creative dream, to write books, could be possible.

Working in PR and advertising taught me how to market my writing so I could sell it. It taught me how to deal with rejection, and how to adapt, how to think of my writing as a business.

Working in libraries taught me how to read. And, through programming events, it prepared me for how many plates published authors have to keep spinning in the air to support our work. Living the dream takes upkeep — professional knowledge that “shadow careers” can help acquire.

Working as a coach motivates me to support myself and my creative practice, so I can authentically support my clients in theirs. I’m not standing in their shadow because I’m afraid of my own light. I’m sharing my candles with them.

Each of these, by Julia’s estimation, qualifies as a “shadow career”.

Yet here I am, a published author — because, not in spite, of them.

Suck on that, Marie and Julia.

III.

The concept of the shadow came to prominence first via Freud, and then through his student C. G. Jung, who would go on to become a bonafide superstar at the intersection of psychology and spirituality.6

In very broad strokes, our shadow is everything about us that remains hidden in the unconscious.

While Freud’s conception of the shadow casts it primarily as a negative (shadow specifically as the unsavory, repressed aspects of our psyche that enact subconscious revenge on us), Jungian analysis has developed over time to apply more compassion — and possibility — to the role of shadow in our lives. Shadow isn’t merely the dark parts of us that we bury, it’s the undiscovered country of ourselves — things we don’t know, but may benefit from seeking out and understanding.

The Artist’s Way’s “shadow artist” concept was conceived within this broader psychological shadow context. Cameron leans too heavily on Freud’s pessimistic take: when creativity is repressed and relegated to the shadow (perhaps when an artist is led to believe art is foolish, or that they’re not an artist at all), The Artist’s Way posits that, “life may be a discontented experience, filled with a sense of missed purpose and unfulfilled promise.”

Yes, repressed creativity breeds discontent. Yes, some choices we make to continue to repress our creativity as a fear response may hold us back. But Cameron’s implication that something like certain creative work we choose to do for money is somehow less than, or distracting from our “pure” creative pursuits dismisses the ways in which a “shadow career” can be an act of creative care, curiosity, and pursuit of self-knowledge.

For Cameron and Freud, shadow becomes a sort of hell or prison, created by negative experience, and our job is to break out.

Jung, on the other hand, called shadow “the seat of creativity,” and made the case for gently bringing Shadow aspects of ourselves to light through Shadow Work, rather than seeking to completely exorcise our dark parts. In 1959, Jung wrote:

To confront a person with his shadow is to show him his own light. Once one has experienced a few times what it is like to stand judgingly between the opposites, one begins to understand what is meant by the self. Anyone who perceives his shadow and his light simultaneously sees himself from two sides and thus gets in the middle.

Why cast out, shame, or judge our shadow aspects when we can meet ourselves, for all that we truly are, right in the middle? Why not perceive our shadow in tandem with the light, and come to know ourselves as people, and as artists, more fully?

A “shadow career” might very well cast light on creative aspirations and abilities that were once unknowable to us.

And to bring us back, for a moment, to the start: a healthy respect and curiosity for our “temperament” — a willingness to engage with the vulnerable, perhaps shadowed and repressed elements of our emotional landscape — may very well reveal new creative avenues and desires to us that can help us alchemise our temperaments into art.

In Writing in the House of Dreams: Creative Adventures for Dreamers and Writers, author Jenny Alexander applies a Jungian lens to creative work:

Embracing the Shadow means opening yourself up to possibilities, letting go of fixed certainties about the Self and the world. It means engaging with complications and conflicts, which are necessary aspects of all creative work.

Our rawest creative discoveries arise when we are willing to accept our full selves — our creative desires, our basic needs, and our dark parts. All of these may live, for a time, in a shadow space: unknown and unacknowledged.

Certainly, by freeing ourselves to creatively express our inner artistry — no matter how bad or unworthy we, or others around us, may deem our efforts to be — we bring our shadows, our repressions, our hidden needs to light.

But I believe we also do that by exploring the very real and valid work available to us as creatives. Would Peggy Olson have become a writer at all, have ever sniffed out her own talent, or unearthed her creative calling, if she hadn’t taken a secretarial job at an ad agency (a quintessential “shadow career” for a repressed writer if I’ve ever seen one).

All this to say, I think Julia Cameron got it wrong, and did me wrong. Her conception of “shadow artists” fails to effectively bring shadow into light. She merely shifts the spotlight, creating shame and repression around one kind of creative life (“shadow careers”) in order to elevate another (the relentless pursuit of a very specific kind of creative dream).

For what it’s worth, I think Mad Men’s Marie got it wrong, too.

It took me too long to grant myself this truth: I can’t have an artist’s temperament and not be an artist. My temperament is the key to the house, and the house was always mine. And I’m taking good care of my creative home, thanks, in good part, to the paycheck my “shadow career” as a writer for hire provides. •

Join the conversation in the comments:

What did this piece bring up for you? I’d love to know:

Has pop culture ever made you question your claim on an artistic identity?

How have you simultaneously followed a “shadow” career path while pursuing your dream?

How has meeting and accepting the Shadow parts of you opened up new creative channels?

Anything else you’d like to share

Support The Shuffle

If you enjoyed reading this letter and you’re in a position to help sustain this newsletter, I’d love it if you’d upgrade to a paid subscription. By subscribing for as little at £1/$1.25 per week, you wouldn’t just be making my day and supporting the hard work I put into writing, you’d also be getting some much-deserved extras from me, including 20% off 1:1 tarot sessions with me, access to creative workshops, and bonus material sent straight to your inbox.

If you’re not in a position to add another subscription to your budget, I get it! You can support me for free by sharing this piece with your friends and followers now — I’d be so grateful for your seal of approval!

Thanks for reading x

I am SO here for bad art. Not mean or evil art, mind you. But “low-standard” art. Let people make shitty shit. Let the process light them up anyway. Let them learn, grow, and discover. Let them discover what good means to them.

I have since gone on to read The Artist’s Way in full, and have returned to it as a reference on the regular for nearly a decade, but I openly admit to cherry-picking my way through the program. Periods of not reading - even for a week - have always coincided with severe dips in my mental health so Week 4 can suck it. Anyway, I am forever a full-time stan for Julia’s six-week program, The Listening Path, which is 100% superior to the Artist’s Way in every way IMO; fight me on it.

Cameron goes on to lump agents and editors into the shadow career category too, which I’m sure was really well-received by her team. She also classifies critics as shadow artists, citing François Truffaut’s assertion that theatre critics are failed directors. As a failed director, ouch. But also, there is simply, undeniably, a shortage of paying jobs for aspiring theatre directors. For out-of-work directors who do pursue critical writing (also a tough creative job to get paid for in its own right), the work allows them to keep their skills and passions sharp, and to stay connected to the industry. Having reviewed theatre myself (often for free, as a way to engage with a craft I love), here’s the truth: we really want the shows we have to sit through to be good, actually.

I also think the whole concept of “shadow careers” denies the rich ecosystem that perpetuates creativity: curators, agents, teachers, therapists… these jobs actively contribute to the creation of art, and we should celebrate that instead of wagging a finger at these people for not pursuing their “real” artistic dreams.

Irony of ironies, it was a debut author I met through my job at BuzzFeed who put me on to The Artist’s Way in the first place.

For more in-depth reading, I highly recommend The Artemisian, where Alyssa Polizzi has curated a wealth of resources on Jungian Psychology and Shadow Work.

I regularly question the use of the word 'creative'. Too often, it's applied solely to people involved in the 'making' of art, whether that's painting, writing, crafting, etc. Yet I would watch my dad, a structural engineer by trade, have to apply the most creative thinking to get the maths to work for a building so it would be safe to use (he also loved doing that work, and he still loves 'engineering' things around the house).

So all of the things written off as 'shadow' careers actually all still involve creativity. I always wanted to write fiction but found people only took an interest in what I did when I started a podcast, because they liked the research I did and how I fitted it together - which often requires finding a thread and coalescing everything into some semblance of sense. I teach at a design school and I'm often written off as the research nerd, as if writing and audio production isn't also creative, and there's this weird hierarchy of what's considered 'valuable' creativity (which is often tied to artistic output) and what is 'supportive' of that. But you can't have one without the other anyway.

In many ways, yes, the bureaucracy of "work" does tend to stifle many a creative impulse and drag us into the purgatory that is meetings and emails in an endless loop. And yet, why can't we all claim creativity in our jobs, even if we're not covered in paint or delving into fictional worlds? Connecting with people is creative work. Coding is creative work. Childcare is creative work. Manufacturing is creative work. This is something I've been thinking about as I navigate my seemingly disparate artistic impulses and day job (librarian). And then I realized that rather than resign myself to my job, or quit it and attempt to make a living off my art, I can do both and consider everything I do to be creative - it's radically changed my relationship with my job, my artistic work, even doing chores at home! Laundry is creative! Cooking is creative!