Once upon a time in Egypt, the secrets of life, the universe, and all the wisdom and power of the human soul were distilled into a series of images and painted onto a deck of cards, preserving them as a sacred occult language used to access the Divine.

The cards were secreted from Egypt to Italy, where they were embraced by mystic sects of the Catholic Church. In the 14th century, when the Papacy briefly moved from Rome to Avignon, France, the cards made the journey too. But somewhere along the journey, they fluttered from their safeholds and found their way into the hands of the masses who misappropriated their rich imagery for game play. Jeu de tarot and tarocchi became popular parlour games — shallow entertainment for Renaissance-era nobles.

The cards’ sacred secrets were lost until, in the 18th century, one man recognised them for what they truly were: not a game, but a divine inheritance. To study and read from them presented an opportunity to rescue occult knowledge lost to the millenia… to travel through time, space, and dimensions and connect to the raw magic of the universe.

It’s a juicy creation myth. One I’d love to believe, given my passion for magic, my profession as a tarot reader and my domicile in Avignon, the very city where the tarot’s secrets supposedly leaked out.

But it’s a story with a clear author: Antoine Court de Gébelin, a French writer who claimed, without any evidence, to have discovered the true origins and interpretations of tarot cards.

“It took fifteen minutes for Gébelin to examine the deck and declare it Egyptian,” Jonathan Allen, co-curator of Tarot: Origins & Afterlives, told me when I visited the exhibition at the Warburg Institute in London last month. “Those were the most important fifteen minutes in tarot history.”

Here begins a dual history that has followed the tarot into the modern era: its mythic reputation as an esoteric tool, and its creative legacy as what the exhibition calls a “story machine.”

For me, too, the tarot is a story machine: a portable, customisable inspiration tool that requires no charging and no wind up — just a shuffle and some trust in the process. Sacred in its creative possibilities, not so much in its concealed esoteric wisdom. For me, divination isn’t prediction, it’s exploration, it’s creative visioning.1

A fabrication like Gébelin’s Egyptian myth, and increasingly abstracted creative interpretations of the tarot may deviate from “the truth” of the cards’ purpose, history, and meanings — but if the cards are the cogs of a story machine, then the truth is rightfully eclipsed by the infinite fictions created when we engage with the tarot, not as a singular object with one definable history but as a device that generates unlimited pasts, presents, and futures.

At the turn of the 20th century, the plot of the most popular tarot story thickened when a secret magical society rose up in Britain. The Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn used tarot in its core practices, drawing heavily on foundations of Gébelin’s Egyptian creation myth. They embellished the story with their own inventions, imagining new connections between the cards’ existing symbolism and numerology, astrology and Jewish mysticism — more stories, more mysteries, more possibilities emerged.

In the early 1900s, Arthur Waite, a prominent member of the Order commissioned the artist Pamela Colman Smith to design and illustrate a new version of the tarot. The Rider Waite Smith deck introduced the first “modern” divinatory tarot deck to the public and assembled a canon of “traditional” meanings for the cards which many new tarotists work to memorise today.

In the Rider Waite Smith deck, each card tells at least one story, articulated through Waite’s own interpretations of the images as recorded in The Pictorial Key to the Tarot and — arguably more importantly — through the images themselves. Smith’s illustrations apply the same level of narrative detail to the 56 Minor Arcana cards as it does the 22 Majors, abandoning the minimal pip designs of the popular Marseille tarot tradition and expanding on the more figurative legacy of the much older Sola Busca tarot.

I wrote about Smith’s contribution to the creative history of tarot in my book, Tarot for Creativity:

Smith’s artistic interpretation of each card literally changed the game for tarot. Instead of relying on memorization and vague fortune-telling codes to interpret the cards, readers could use Smith’s deck to take their tarot storytelling to a whole new level. Thanks to Smith, most modern Minor Arcana images invite us into the heat of action. They’re a powder keg for intuition’s spark. They are epic stories neatly packed into the palm of your hand.

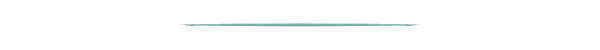

Later in the 20th century, an ousted member of the Golden Dawn made his own crucial contribution to the story of tarot as we know it today. Aleister Crowley published The Book of Thoth (Egyptian Tarot) in 1944, alongside a deck co-created with the painter Lady Frieda Harris.

As the title suggests, Crowley and Harris’s tarot borrows from Gébelin’s myth. Its overall design is inspired by Egyptian mythology, reinforcing the powerful impact a good story has played on the tarot’s evolution. But Crowley and Harris took plenty of creative license, drawing on ancient and modern legends to tell their own unique story through the cards: their Fool resembles the ancient Celtic Green Man, while the style of Harris’s take on the Tower shares (to my eye anyway) compositional DNA with Picasso’s Guernica, painted in 1937 — a year before Crowley and Harris set to work on the deck.

Working around the same time, but independently from the Golden Dawn, the artist Austin Osman Spare began work on his own, deeply personal version of the tarot. But it would be a century before his contribution emerged as a critical character in the tarot’s creative history.

Spare’s take on the tarot holds a special significance at Tarot: Origins & Afterlives. It was the exhibition’s co-curator Jonathan Allen who rediscovered Spare’s cards at the Magic Circle Museum in 2013, and subsequently published Lost Envoy: The Tarot Deck of Austin Osman Spare.

Lost Envoy is an example of tarot-as-story-machine in action — the remergence of Spare’s tarot became an opportunity for storytelling. Within the book’s pages, contributors including comics writer and occultist Alan Moore, novelist Sally O’Reilly, illustrator Kevin O’Neill, and multiple Spare biographers and researchers offer their interpretations of Spare’s artwork, their stories of Spare’s life and work, and, in O’Reillys case, a fictionalised encounter between Spare and the suffragette Sylvia Pankhurst.

In the book’s introduction, Allen identifies how Spare innovatively blended the Major and Minor Arcana in his cards, and muses on what could have been — on the stories that we might be telling about the tarot now — if Spare’s deck hadn’t languished, unseen, for so many years:

...[T]he deck blurs the distinction between the two class-bound categories … conflating tarot’s twenty-two familiar trump cards — its ‘Major Arcarna’ — with a ‘Minor Arcana’ comprised of ordinary playing cards. The resulting deck is a hybrid of unprecendented iconographic and operational complexity, one that offers trajectories — albeit in provisional form — which might have significantly altered the historical course of both card reading lineages…2

Viewing the exhibition, I was comforted and fascinated by the fluid relationship modern artists seemed to have with the tarot as both an esoteric object and a creative project.

In a letter on display at the exhibition, Pamela Colman Smith — a practicing member of the Golden Dawn herself — describes her work on Arthur Waite’s tarot as “a big job for a little cash — a set of designs for a pack of tarot cards.” She offers to send her friend a few of the original drawings, as she suspects that “some people may like them.”

Also exhibited are correspondences between Aleister Crowley and Frieda Harris, debating their shared vision for the deck and offering unique insight into the deliberate creative process behind an object so often cloaked in spiritual mystery.

Following the Thoth display, the exhibition moves readers into the 1970s, where a copy of Italo Calvino’s The Castle of Crossed Destinies lies open.

It’s in this room, where Calvino enters the picture, that the exhibition first uses the word “story-machine” — and for good reason.

Allen explained to me: “The jump from Crowley to Calvino was a crucial conceptual moment within the exhibition as we moved from thinking about tarot as a way of synthesising different magico-religious practices, to tarot being deployed by artists as a protean creative tool.”

The Castle of Crossed Destinies is the illustration of tarot-as-story-machine. Set at a dreamlike dinner party, guests must draw tarot cards and use them to tell stories. What follows is a collection of tales generated based on cards in the deck. In “The Tale of the Alchemist Who Sold His Soul”, the Ace of Cups and the Popess (High Priestess) inspire one guest to spin a story in which a man seduces a nun by a fountain in the woods. In “The Waverer’s Tale”, Calvino weaves a love triangle inspired by The Lovers, from which the protagonist never fully escapes: the Two of Clubs (or Wands) dramatises his false decisiveness and captures the lifelong “what if” he carries with him.

Of course, the tarot’s narrative function predates Calvino. Cartomantic readings — psychic, self-reflective, or otherwise — have always been about storytelling; connecting the dots between cards is a creative act in its own right. But Calvino’s work formalises and documents the creative process inherent in a reading, showcasing how the act of pulling cards and divining stories from their imagery isn’t merely a fortune-teller’s pursuit, but an artistic mission.

The tradition of using the cards as tools for structuring and generating fiction has gone on to develop its own legacy in literary history: novelist and memoirist Alexander Chee has written about using tarot spreads to develop characters, the tarot expert Rachel Pollack was also a prolific novelist, and the soon-to-be-published novel, The Tarot Reader of Versailles by Anya Bergman draws on tarot both as a historical inspiration and a structural one: her chapter titles follow the Major Arcana sequence, and she breaks sections up with original tarot spreads that tie into the story.3

We can look back to Spare’s cards as another concrete example of the tarot functioning as a “protean creative tool”. A work-in-progress, the deck offers unique insight into Spare’s conception of the tarot as a divinatory tool alongside the evolution of his creative process and vision for the project.

Allen imagines Spare’s usage of the cards Lost Envoy:

Spare’s cards take the form of what appears to be a self-instructive deck, one perhaps simply created due to the unavailability of a commercially printed deck. In the hands of an artist as gifted as Spare, however, even a ‘training deck’ — if that is indeed what the current deck represents — was an opportunity for his vision to roam more widely. The resulting cards seem to have become a studio-in-miniature in which the young artists processed the wide range of stylistic and philosophical influences shaping him during the period.4

In our conversation, Allen observed that “Spare’s deck has the feel of a psychological self-portrait.”

Spare wasn’t the only creative to seek out, find, and represent himself in the cards.

To name a few examples: Salvador Dali used his own likeness as a model for his version of the Magician card; Tarot: Origins & Afterlives features photographs of Calvino posing as The Magician, and in The Castle of Cross Destinies, the writer documents which specific cards he identifies with his own creative personality; the dark, windswept hair of the the dancer in surrealist painter and novelist Leonora Carrington’s version of The World in her Major Arcana paintings bears a striking resemblance to her self-portrait’s wild mane.

Artists aren’t just using the tarot to look within, but to look beyond themselves to provide fresh perspectives on the world around us, too. The exhibition presents paired card designs from Suzanne Treister’s Hexen 2.0 tarot, and its recent update Hexen 5.0, both of which appropriate tarot archetypes to “envision positive alternative futures for our complex, hyper-technologised world.”5

Today, tarot’s reputation as a creative endeavour is approaching an eclipse of the cards’ esoteric identity: exemplified in the exhibition’s final room, the Tarotkammer.

In this cabinet of curiosities, the curation team brings together a range of contemporary tarots — from Sharon Gal’s Etudes, an abstraction of tarot archetypes into words and colour alone, to the Dust II Onyx tarot which works to address the lack of Black representation in historic tarot decks, to the Unreasonable Silence tarot which reimagines the tarot through an absurdist lens.

These creative departures symbolise the new creative liberties available when we come to the tarot as a portable creative studio — a site of possibility, rather than some divine dictation, frozen in our imaginations alongside the Pyramids. The tarot’s gradual demystification has, in Jonathan Allen’s words, “allowed artists to integrate tarot within their own processes and has encouraged their co-production of the form."

There is no “canon” in tarot anymore, only possibilities. Gébelin’s myth no longer monopolises the mystique of the cards, and now exists as just one facet in the infinite stories we can tell about and through the tarot — and the unlimited stories it can tell us.

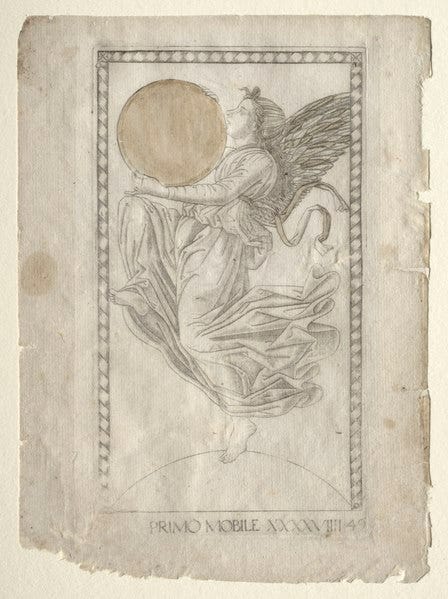

The tarot may not hold ancient secrets of the universe, but that doesn’t mean there aren’t mysteries to solve: in our conversation, Allen cited the origins and function of the so-called Mantegna tarocchi — a series of 15th century engravings which share some visual overlap with tarot imagery — among one of the most vexing questions he’s still left with.

Since its discovery, the Mantegna tarocchi has been previously misattributed to the artist Andrea Mantegna and mistakenly associated with a tarot’s lineage as a card game.

Perhaps, in the end, these mysterious images were born from creative pursuits, too. Allen offered some evidence to suggest their use by Renaissance artists as a kind of visual encyclopedia.

In this way, maybe the cards’ unique magic has been with us since the dawn of time. Maybe the universe’s secrets have been distilled into images that pique our curiosity and make us feel connected to some mythic power. But maybe that power has always been the human creative force — the story machine that doesn’t so much see the future as it does create it. •

Join the conversation in the comments:

What did this piece bring up for you? I’d love to know:

Have you visited the Origins & Afterlives Exhibition?

What is your favourite story about, or inspired by, the tarot?

Support The Shuffle

If you enjoyed reading this letter and you’re in a position to help sustain this newsletter, I’d love it if you’d upgrade to a paid subscription. By subscribing for as little at £1/$1.25 per week, you wouldn’t just be making my day and supporting the hard work I put into writing, you’d also be getting some much-deserved extras from me, including 20% off 1:1 tarot sessions with me, access to creative workshops, and bonus material sent straight to your inbox.

If you’re not in a position to add another subscription to your budget, I get it! You can support me for free by sharing this piece with your friends and followers now — I’d be so grateful for your seal of approval!

Thanks for reading x

My own books, Tarot for Creativity and A Writer’s Guide to Crafting Stories with the Tarot can operate as user manuals for mastering tarot as a story machine — through reflection on the cards’ imagery, tailored creative prompts, and tarot spreads designed to customise the creative tarot experience.

Here at The Shuffle we dip into the tarot’s functionality for storytelling on the regular, and I like to believe that all of my work stands as an example of creative work the tarot can produce — proof of concept for the story machine.

Lost Envoy, p. 17

I had the PLEASURE of reading an early reader copy of The Tarot Reader of Versailles, which I took along as my date to the exhibition.

Lost Envoy, p. 17

Quote from curational context displayed alongside Treister’s artwork at Tarot: Origins & Afterlives

This was fantastic. Thank you for putting in all the work to do it!

Awesome article. I appreciate how much information & insight you processed & shared here! I feel so informed after reading. Did not know Alistair Crowley (from Gaiman’s “Good Omens”) drew his name from a real person. It’s also strange to consider the tarot idea as we understand it is a 20c convention. And the storytelling aspect of tarot made me think of tell-a-story cards I bought my kids when they were little. https://a.co/d/6YAdBub. Finally, cannot help but note your use of “generative” here in light of AI.